Cult 1960-70s Yugoslav animation series holds timeless lessons for innovation

Decades before Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos opened up space for tourism, an eccentric Croatian gentleman and one-time adviser to the British government had already enabled space travel for the masses, in a washing machine powered with a colourful pin-wheel.

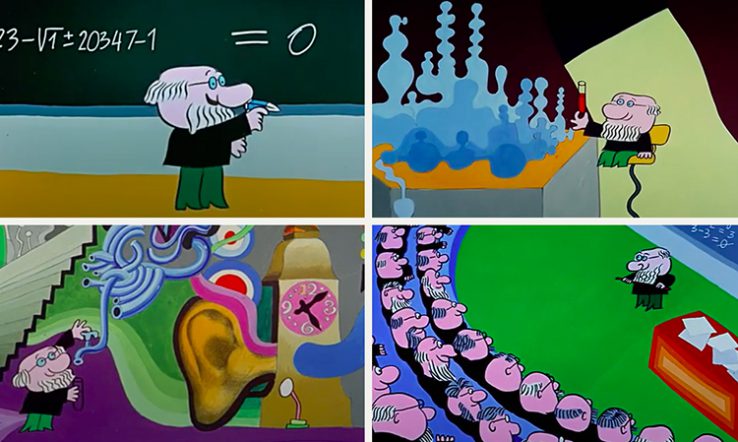

The public travelled to a beautiful pink planet to hear an alien singer perform in a quartet with Earthlings, although admittedly all in the cult Yugoslav animation series from the 1960s-70s, Professor Balthazar.

The episodes, in a nutshell, are Balthazar encountering a problem, thinking about it, then running his invention machine to fix it, resulting in a happy ending that restores “harmony and joy” in what is perhaps an allegory of the happy socialist society Yugoslavia’s people aspired to.

But close watching of the series, which is a popular science NGO in Zagreb expects to make freely available soon for the first time, reveals a more complex picture that still holds valuable lessons about the purpose and travails of innovation.

Created by Academy Award nominee Zlatko Grgić, the series dates back to the golden age of the renowned Zagreb Film animation studios. The character of Balthazar still enjoys widespread popularity in Croatia, featuring at cultural events and even in primary school textbooks.

The things that make it enjoyable to watch for adults, too, are unpredictable plotlines and humorous references: for example, a potted cactus falls on the professor’s head and triggers a Eureka moment, Isaac Newton style; and when aliens make their way to Earth, it’s not on flying saucers but on flying tea spoons.

Beyond the enduring appeal of its humour and simple yet skilled animation, many of the lessons communicated by the series remain relevant today.

Place and people

Take the issue of ‘levelling up’ and using R&D to ensure local prosperity, which is very much a contemporary concern. Balthazar was all about local issues, regularly innovating to improve his city, the colourful ‘Balthazartown’, for the benefit of its citizens—and often only after being approached by them to do so.

Other people’s sadness and suffering are often triggers for his inventiveness, leading him to come up with contraptions such as “the melody-pede”, a musical exercise bike to help an overweight policeman lose weight, and “a strange and wonderful firefighting device” to help clumsy local firemen do their work safely and happily.

His other inventions include “a miracle ointment that makes everything grow faster” to boost agricultural yields, and “the quick-growing underwater tree” to stop sawfish from damaging the town’s bridge.

Sometimes his inventions improve working conditions and productivity, like when he modernises a craftsmen’s workshop with a robotic system that does their work for them, allowing them to slack off, or when his little robot ‘Alfie’ replaces the night watchman at a factory so that he can rest.

This theme comes up repeatedly, as when his ice cube machine, the snow-o-mat for polar bears, allows the zoo keeper to nap at work instead of working hard all the time. The machine “made life much more pleasant” for the zookeeper, we’re told. Innovation is seen here as something that can boost productivity and improve wellbeing at the same time.

Climate change

Balthazar is frequently forced to innovate to deal with forces of nature—most often extreme weather such as floods, droughts and high winds, as well as pollution, all of which are still very much in science and technology’s sights.

The series depicts the frightening impact of extreme weather: in one episode, Balthazar is almost killed by a lightning strike during heavy storms. There is also a belief in technofixes, such as Balthazar’s “turbo jet sucking machine” to take away fog, or his instant sun umbrellas to protect from excess sun.

Or take his “smoggyex”, a giant air purifier that turns pollution into free fuel for cigarette lighters, or his giant windmill that pumps floodwater and stores it in the portable form of tinned clouds.

These inventions have in common circular-economy-style processes that recycle unwanted or harmful materials and turn them into usable and beneficial products. They also often appear to be free and don’t create wealth for the inventor, which might reflect socialist politics of the time.

Indeed, the professor’s flying pretzel mill delivers free pretzels around the town, and the “ear-water-shaker” invented to help out a local weatherman later becomes a free “major attraction” at the local beach. Similarly, his wig-o-mat churns out free wigs for aliens, and the knit-o-mobile supplies free eight-armed sweaters for fashionable octopuses.

Arts and humanities

Some of Balthazar’s work perhaps falls under social sciences or arts and humanities, which are subjects that are currently making a strong case for their importance in a world dominated by the pursuit of profit and economic returns.

In one episode, for example, he invents “good will” to solve the issue of bullies who descend on his city. In another, his “laughter-sprinkler”—a flying happiness dispenser—rids the city of a black cloud of malice that makes people argue. Sometimes Balthazar just listens to people’s problems and offers some words of advice, or locates answers in ancient texts.

In some episodes, his inventions are there for pure joy, as in the case of his rainbow maker invented for the town’s “festival of beauty”. This is art for art’s sake.

Elsewhere, the professor underscores the importance of mathematics, for example by using it to lecture on his work in London, where we see a long calculation on the blackboard behind him. Or, when he proves mathematically that an alternative world exists in which people can live freer and happier lives, the narrator tells us: “He calculated scientifically and he found the proof that such a world existed.”

Science diplomacy

Balthazar’s work sometimes takes him abroad: for example, to speak to a packed lecture theatre in London about the “use of fog for peaceful purposes”. Balthazar then saves the day as an adviser to the British government by fixing Big Ben.

He goes on to refuse “all of the rewards and honours offered him” and only asks for a small favour to help out a friend, Igor the mouse, who wants permission to settle permanently in Big Ben (Parliament grants his wish).

Here, the series demonstrates the soft power of science and the role science diplomacy can play in solving problems, something our more fragmented global politics arguably needs more than ever.

Failure

But it’s not all smooth sailing for the “famous inventor” and his “miraculous machine”. The popular view is that Balthazar quickly solves even the toughest of problems, but many episodes see him struggle to find a solution. Sometimes he must work in his lab for days on end before he’s able to invent something.

His “thinking got stuck” when he missed his breakfast. He sometimes forgets things and is “confused” when confronted with some challenges. He doesn’t always know the answer immediately and occasionally makes “a slight error in the calculations”. His “infallible method” goes “wrong”, and in one episode we’re told “Professor Balthazar had failed” when his invention ends up having unintended consequences.

Such examples demonstrate the fallible nature of innovators, and difficulties embedded in scientific discovery and technological development, as well as potential unintended side effects of technology, all issues that are still very much alive today.

Political system

Reflecting Cold War rivalries, there is an occasional dig at Western capitalism: some of Balthazar’s achievements rival and, in fact, go beyond Western ones. He invents a windmill bigger than those in Holland, and his Ferris wheel was even envied by the Viennese, we’re told.

With the rapid rise of communist China as the world’s science and technology power, similar questions are being asked now about what type of political and economic system best utilises R&D.

Alongside socialist propaganda, Balthazar carries some anti-capitalist messages, such as when a fat cat financier and his wealth disrupt the harmony of the people, leading them to fall out and fight over money.

Balthazar also advises a rich but depressed apple producer, who used to be homeless, to rediscover the simple life by going to a desert island, only for the man to launch a major banana business there and end up overworked and depressed again.

The capitalist system is deemed “an endless devilry” in the very last episode of the series, where traffic exhaust creates a literal pollution monster in the city. Balthazar invents a special filter that cleans the air, and happily gives his designs to a rich businessman to mass produce it—but this mass production in factories then pollutes the air, recreating the initial problem!

So the series holds many lessons, from the nature of discovery work through to potential pitfalls of innovation. Its timeless topics and style mean it is widely relatable, and it can be enjoyed for its visuals and gags while also acting as a starting point for discussion of some the key issues surrounding science and technology.

With the rising need to get more people educated in the sciences, and more staff into the R&D workforce, this cartoon could be another tool in the communication arsenal for enthusing more children and adults about the magic of science. Hopefully it appears online soon.

Mićo Tatalović is a news editor at Research Professional News. His in-depth review of the cartoon series will be published in the next issue of the Journal of Science & Popular Culture